Your goal is not "zits on a map."

I'd never heard the expression for pins on a map until mapping 70,000 stories.

Now I've mapped 335,000 stories projecting history and points of interest geospatially. As I dove into 40,000 hours of mapping, that line got bigger and bigger. Did I really want more zits to show?

I started with a map of just one block in Greenwich Village which I physically circled many years, growing the "zits." Collecting 100s of stories on one block, aiming for a story in every building. But a pockmarked map was clearly not the best way to narrate the geography.

The "zits" became more of an eyesore as I started to cover all of Manhattan and then journeyed worldwide, landmarking stories.

On a sidebar, I filled out tweet-sized story bullets with profile, topic and geo tags. But even scrolling text like Twitter was cumbersome to explore geography.

The best experience was staring at automatically-changing photos, showcasing someone's journey. A scrapbook of images travelling a route. Windows into a biography or topic (Noodles, Pizza, Soup, Patti Smith, Anthony Bourdain etc). It felt like walking the earth, keeping places alive. Not dead on a map.

You could imagine so many visual experiences for voice command. Show me Keith Richards nearby or in Paris. Show me Rock and Roll in Nashville.

No different than social media, we look at pictures most and longest in duration in digital media. There's no competition from a map or even a streetview. Photos rule for both engagement and traffic conversion.

In a social media, where I share geographic stories regularly to 114,000 followers in NYC, it's obvious the engagement starts with a photo, especially one that is nostalgic, recognizable personally and cool. Something that triggers memories or a desire for exploration.

On top of this, I got into deep map literature.

A geospatial layering of interesting history by address by street. Here are stories you never knew on this street, even if you lived there. I try to stitch stories thematically to show a "geo-pattern." Here are my notes identifying notable addresses bundled by theme (e.g. music history), showcasing the regional identity of The Bowery:

A map, however, first only shows you places you might already know. In this case, just one street, The Bowery. A lot of visual redundancy would be in that viewing experience.

Then there's the homogenous looking pins not reflecting the diversity or level of interest inside each point of interest. Pins are no match for headlines or photos. They're callouts but you're being asked to click each one in the primary view. This map of pins tells you nothing yet about The Bowery and shows a street you might already know. The primary layer has no added value:

Though not obvious at first, for someone who passionately uses maps everyday to hunt for addresses (or for other research), over time it became very clear maps ironically do not draw traffic as much as other consumer content.

We look at a map primarily for research, not pleasure. Only if we need to know where something is or was. At some place, possibly unfamiliar.

That's not 24/7. It's not even for 1 hour. It might only be for a few seconds. Or, if you already know where all the streets are in Manhattan, you might not even need a map.

Maps might look more interesting than pinned content as a primary view if what's behind the pin is less interesting than editorial or social media. But what if the pinned stories are more compelling? Shouldn't we show why a story is interesting inside each pin first? Pins are not pitching Points of Interest well. What do these pins tell you:

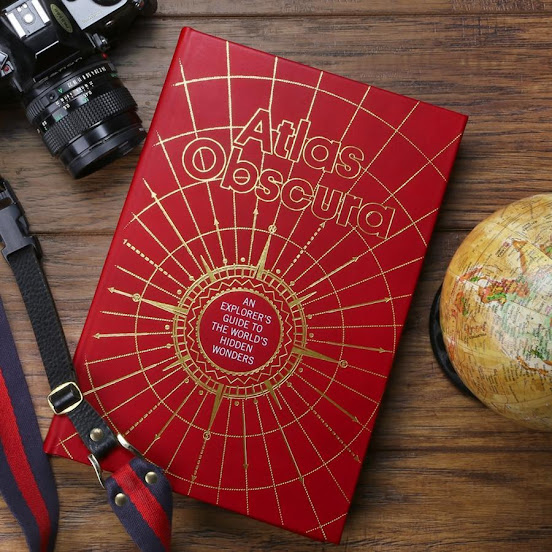

Don't get me wrong. From childhood, I loved street maps, atlases and globes. But if I were honest, I loved songs, photos and stories far more. And maps stayed stagnant. The more familiar you got, the less interesting a map became.

OK, admittedly, I liked spinning it more than viewing it. Like popping bubbles on packaging (which is similar to popping pins).

During the pandemic, I got rid of my data services because we had the world's longest lockdown. I had to stop for directions once and got guided to a crossroads where he said be sure to try the burger and milkshake there. Something my GPS could not even tell me.

What a selection for discovery:

What I found is that I could survive without GPS to head to a new destination. I only got lost once, but it forces you to meet people, locals, and ask for directions. This local once lived where I was headed and had stories to tell.

I had to prep longer looking at streetviews to familiarize myself with visual beacons. I also had to write down instructions. And even then, I only spent 20 minutes at most looking at a map. I am spending more time writing this.

Being mapless by phone did make driving more pleasurable. I paid more attention to the road in front, the scenery and visuals, looking for beacons, more than I normally would. I was no longer traveling with blinders, relying on convenient GPS. My eyes were wide awake.

That became a refreshing novel experience for me - or more accurately a renewed experience.

In cartography, a map is a geospatial projection, but it doesn't have to be a roadmap, showing you what you already know or don't need.

Photos (with soundtracks even) can be projected geospatially, like windows into a place or journey. A smarter streetview deep mapping geography with layers of interesting stories.

To generate traffic, the best content has to be projected. Content one needs first, for pleasure.

So the goal is the reverse of many mapping communities. Zits on a map are last for research. The content hidden by the pins are first.

They also need to be organized intelligently for exploration. For viewing and publishing.

Cartographic blogging can draw traffic in a compelling way. But not if "zits on a map" are the primary interface.

You can zoom in for even more zits on the block. But you can't see any narration for the block, unless you click several times. This violates a cardinal principle of hierarchical navigation in user experience design.

The primary layer needs to achieve an end goal ideally, engaging without leaving the page. Imagine if you kept on being required to click or leave Instagram. You would no longer be glued to it as a viewer. Even in map tech presentations, people zip by the zits, faster than a weather reporter.

But in great storytelling, a storyteller holds you captive to the stories. That's when cartography becomes more frequented as consumer product.

Spotifying the Map is a good metaphor.

Songs are intelligently playlisted for experiencing music. You don't even need to read much, the music just plays. If need be, you can search, explore, read and click to hear. Song metadata is not covered by pins.

GPS experiences - geospatial experiences - should be like soundtracks. A rabbit hole easy to experience.

Maybe it's a jukebox of postcards, visually compelling with ancillary notes and maps when desired. Just tap to see the back. The primary layer shows you what you might be interested in. The pin just covers a map, covering what you already know is there. It's not a mystery door.

Maps can still be accessed to show patterns of someone's life or a group of people's lives like these pinned strings behind Feist. But the primary attractions are the stories, images and music of Feist -- pitched first.

Cartographic digital gardening is needed to display what people want to see first for pleasure.

There are tremendous possibilities for intelligent connectivity between collections of stories so when I'm exploring jazz in Paris, I might be taken to St Louis too or a cool personal jazz record collection or cool jazz photos, all geographically mapped but connected by correspondences. Cool exploration routes.

Geography can be playlisted meaningfully. Bucket-listed and scrap-booked. Linked to other cool collections. It's about designing the cartographic collection first (a new visual map) that pitches what is interesting.